An article memorializing Prince Twins Seven-Seven, who spent time as Artist in Residence at Material Culture and passed away last June, appears in the spring 2012 issue of African Arts. We received permission from the author, Henry Glassie, to post it here to commemorate the anniversary of his death. A pdf of the full text, complete with original photos, is also available online.

In Memoriam: Prince Twins Seven-Seven

1944–2011

by Henry Glassie

To begin at the end is to begin in sorrow. Prince Twins Seven-Seven died in Ibadan on the morning of June 16, 2011. For seventy-two days he lay in the hospital, unable to move, communicating only by blinking his eyes. It was reported as a stroke, but whatever the cause, it was wrong—the wrong end for an ebullient man of constant action whose body was charged to the full. He beat rhythms on trees in childhood, danced on the road in youth; he whistled and sang while his hand darted and glanced, filling spontaneous shapes with intricate patterns bound for infinity.

Prince was born on May 3, 1944, in Ijara, near the northeastern edge of Yorubaland. His father, Aitoyeje, was a Muslim from Ibadan. His mother, Mary, was a Christian from Ogidi. Prince was, in his words, a “pure Nigerian, to the core.”

His name trapped the attention of the many who wrote about him. As he put it clearly, precisely, his name was Taiwo Bamidele Olaniyi Oyewale Oyekale Aitoyeje Osuntoki. Taiwo because he was a first-born, junior twin. Bamidele was the name his father gave him, hoping he would survive and find his way home to Ibadan. His grandmother named him Olaniyi, an ambitious family name like Oyewale. Oyekale was his grandfather, Aitoyeje his father, and Osuntoki was his great-grandfather, a military leader whose career can be traced through Samuel Johnson’s The History of the Yorubas. His descent from Osuntoki, who served as the king of Ibadan from 1895 to 1897, granted him the right to be called Prince, the form of address and reference he preferred.

That was his name, but when he took to the road as a fantastic dancer, Prince named himself Ibeji Meje-Meje in Yoruba, Twins Seven-Seven in English. Twins, plural, not singular, because he was double, a twin who absorbed into himself the spirit of his twin sister, Kehinde, when she died, giving him the power of a woman as well as a man. Seven-Seven, a repeated seven, he named himself because his mother—called Iya Ibeji, the Mother of Twins, on her tomb in Prince’s home in Osogbo—gave birth to seven sets of twins. Prince was born in the seventh set, and of the fourteen children, only he survived into maturity.

Prince’s paternal grandmother, Morenike Apeshigidibarin, was a prosperous circuit trader. She took her daughter-in-law into partnership, and they bought Prince a fine bicycle and sent him off with loads of goods to sell to women. But, excited by a hit of I.K. Dairo’s, he abandoned trade, bought a gramophone, renamed himself, and broke beyond control, dancing for slight pay through the villages. As a dancer, he joined a traveling medicine show, selling Superman Tonic, a concoction of river water, spice, and caramelized sugar, that was guaranteed to make men potent and women fertile. With the medicine men he came to Osogbo, where he crashed the gate at a literary event in the Mbari Mbayo Club. There he danced, astonishing Ulli Beier, who, recognizing wild talent, topped the salary the medicine men were paying and convinced him to stay.

It was the summer of 1964. Prince was twenty. With nothing else to do, he wandered into Georgina Beier’s workshop. The others were painting, but Prince called for pen and ink, and starting at one corner, he filled a sheet of brown paper with the Devil’s Dog. Ulli Beier was astonished again and later wrote that the picture, the first Prince had ever drawn, already bore “the typical Seven-Seven stamp.”

Within a year, Prince’s work had been shown in Nigeria, Czechoslovakia, and the United States. From that time to this, his work has appeared in international exhibitions at the rate of better than two a year. Most have taken place in the United States; Germany comes next, then Nigeria, then England, and the rest scatter: Spain, France, Italy, Holland, Finland, Czechoslovakia, Ghana, Canada, Mexico, Cuba, Argentina, Japan, and Australia.

Those facts and that list imply a tremendous innate talent, and they suggest the rise to global stature that was confirmed, in 2005, when Prince was named the UNESCO Artist for Peace. But such a celebratory summary, fit to an obituary composed in sadness, slides over the biographical complexities and only hints at the excellence in art that is his legacy.

As one of the young men encouraged and instructed in the Mbari Mbayo workshops that Ulli Beier organized and Georgina Beier conducted, Prince began as an artist of the Osogbo School. He was, some say, the most talented, and he was, all agree, the most distinct. His style, his alone from the beginning, matured swiftly, sharpening as he mastered new media, from pen and ink to etching and painting, until in 1969 he invented laminated paintings on wood, a technique that he called sculpture’s paintings and developed to separate himself from his imitators. In the 1970s, by the time he was thirty, he had become a lone actor: a popular musician and an acknowledged star of African art. He had seen London and New York. He had been featured in Ulli Beier’s Contemporary Art in Africa. African Arts had published two papers about him, one descriptive by the Mundy-Castles, one analytic by Robert Plant Armstrong, and soon Bob Armstrong would praise Prince as the modern master of the Yoruba tradition in Wellspring, the middle volume of his great trilogy on art.

Fame continued on its own arc into the 1980s, while Prince’s life twisted. In July of 1982, he was pulled, unconscious, from a car wreck. The radio announced his death. He was given an artificial hip and confined to bed for eighteen months. His wives abandoned him. With an iron hip and a limp in his gait, his dancing days were done. Work stopped, and in this moment of silence the Western interest in him began its long decline. But, undefeatably energetic, he was back at it by the age of forty, and as he slowly regained his power, he found new patrons among the Nigerian elite. It had always been the case that what Prince wanted from foreign acclaim was fame at home, and now he had it. Local men of wealth were commissioning paintings, and the boys in the streets who loved his music greeted him, shouting, “Seven-Seven is the number.”

Recovered and active once more, Prince was proud that, during the 1990s, his work appeared in major exhibitions in Spain, Finland, Mexico, the Netherlands, England, Germany, and the United States, but his life reached its peak with the award of high chieftaincy titles in Nigeria. In January of 1996, he was named the Ekerin-Basorun and the Atunluto of Ibadan. In December of the same year he was named the Obatolu of Ogidi. With these chieftaincies, two in the home of his father, the third in his mother’s place, success was his. At the age of fifty-two, he could relax in his power, but success came coupled with distress, with social obligations that pulled him away from painting, with constant demands on his status and finances, with troubles at home, troubles with the police, with armed robbers, troubles in the vexed sphere of politics, and, overwhelmed, he escaped to America in 2000.

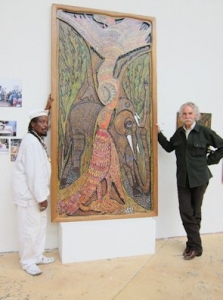

His plan was to settle permanently in Philadelphia, where he had been garlanded with honors in the past and had a loyal supporter in Harriet Schiffer. Prince began with an immigrant’s hope, met with an immigrant’s defeat. He was swindled, evicted from his house, fired from a succession of menial jobs, and—bankrupt, jobless, and uninsured—he was nearing despair, feeling, he said, as though he were tied up in a sack and sinking in the sea. At this lowest of low points, through a chain of chance, George Jevremović entered his life, as Ulli Beier had exactly forty years before. The proprietor of a vast emporium named Material Culture, George Jevremović mounted an exhibition for Prince in 2005, struck a generous deal with him about profits, and gave him a place to work in comfort and at his own pace.

The artist’s life, Picasso said, is not one of smooth evolution, but of “certain ups and downs that might occur at any time.” Prince was an expansive man, game for fresh challenges, and his artistic career pulsed through periods of high and low productivity. During the 1960s and 1970s, when his style consolidated, he was distracted by his simultaneous success as the lead singer in a popular band. The wreck in the 1980s and the chieftaincies in the 1990s interrupted the flow of his art, but he knew moments of high productivity late in both decades. Miseries in America stilled his hand, but once he had his own studio at Material Culture, he entered a phase of robust creativity, as vibrant as that of his beginning, which lasted from 2005 to 2008. He sold an old work to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, found buyers for a few of his new masterpieces, but he never understood, he said, the system under the flash of America. His money ran out. Prince was not bitter, but America has beaten him. He returned to Nigeria in June of 2008.

Prince went home with a hope. His dream was to be, as his great-grandfather had been, the king of Ibadan, to be known to history as Osuntoki II. A step toward that goal was to become the Mogaji, the head of his family, the chief of the clan. The old Mogaji, Chief Busari Odunoye Osuntoki, a gentle elder who ruled from Olosun compound in Ibadan, died in March of 2008. Prince was one of two eligible candidates, and he was selected by his family to become the new Mogaji. It fell to the king of Ibadan to set the date for Prince’s coronation. The event was planned, then postponed, and Prince waited. He returned to the United States in June of 2010 for a massive exhibition, including works from the whole of his career, at Material Culture in Philadelphia. Then he went home again to wait. Dates for the coronation were set and canceled, set and canceled, and Prince was still waiting when the darkness came down. Nothing is certain, but as I write, a memorial service is being planned for August of 2011 in Osogbo.

The fragile chronicle of Prince’s life seems to slip from chance to chance. Suppose Ulli Beier had not come to Nigeria in 1950, or Prince to Osogbo in 1964. Suppose Prince had avoided the wreck in 1982, or missed meeting George Jevremović in 2004. It could easily have been so different, but in Prince’s mind the pattern was firmer, clearer.

Before his birth, Prince chose his head, the head of an artist, in the garden of the creator, Obatala. In boyhood, he sang the strange songs that rolled in his head; he raised castles of sand and watched the ants, learning their incremental mode of creation. Whatever the circumstances, he would have built his life out of art. That was his infixed, elective destiny.

Prince came to the earth as an abiku, a child born to die. Sent by the spirits to torture his mother, he came and left six times, each time as one in a pair. Before his seventh birth, the babalawo told his mother that the solution to her problem lay close at hand. This time, when she was pregnant, she went to a lake a short walk from her house in Ijara, and drank its water, the water of the goddess Osun. Her boy lived, and when he was ill, she gave him the same water to drink. Prince survived: he was, you see, the reincarnation of his great-grandfather Osuntoki, whose name, Osun-toki, means “Osun is worthy of worship.” Prince’s repeated returns were an embodied request, made by his ancestor to his mother: she, though a Christian, should honor the familial obligation to venerate Osun, the goddess of the sweet water, the deity of fertility, health, and prosperity. When mother Mary turned to Osun for help, her boy at last remained on the earth. With that victory came an obligation.

The demand of the spirits, who had repeatedly sent her an abiku child, was for Prince’s mother to acknowledge their power, as she had Osun’s: if her boy lived, she had to humble herself by begging and dancing in the streets. A prosperous trader, she refused, and her duty shifted to her healthy son. He danced for money in public, paying off her debt to the spirits, and as he began to replace the new faiths of his parents with the old religion of his people, the Yoruba, Osun led him to her place, to Osogbo, a city on the banks of the River Osun. There he fulfilled his destiny, becoming a musician and a painter. And there he assisted Susanne Wenger in the restoration of the shrine to the goddess, where thousands gather every August to worship Osun and drink the water that ensures fertility, to take into themselves, sacramentally, the water of the river that is Osun herself.

As Prince drove from success to success in the city of Osun, the dilemma of his existence was set. By virtue of his incorporation of his sister’s spirit, he was both male and female. He bore within the powers of Sango and the powers of Osun, who were, as Prince told it, husband and wife. His eternal, internal struggle was to subordinate Sango’s red powers to the white powers of Osun. To that end, once he had come to self-knowledge, he always wore white, white robe and underclothes, white socks, white shoes. When the white powers prevailed, he was endlessly creative, effortlessly making painting after painting. At work in solitude he became a famous painter. With fame, the red forces rose. A charismatic, extroverted man—flamboyant was his word for himself—he was sucked into the social swirl, delighted by adulation, drawn away from art, and tempted by the political entanglements that could carry him, like Sango, toward worldly power.

The spirits had warned him. Late in the 1970s, Prince had become active in politics, first at the local level, then at the national. In 1982, he was coming home from a political meeting, when he swerved off the narrow Gbonga-Ikere Road to avoid a head-on collision, plunging into the bush and crashing into another car. The spirits nearly killed him, he said, to warn him away from politics, to keep him focused on art. But the Sango within could not be checked. Prince ran for office again and, accepting high chieftaincies in the places of his parents, far from the compound he had built and decorated in Osogbo, he became so enveloped in obligations, so ensnared in troubles, that he fled. Osun directed him to Philadelphia, a city set between rivers, where he had brought new people to knowledge of the goddess in the past. It was hard, but in time—removed from the enticements and encumbrances of Nigeria— he fully recovered his artistic energies. Then she brought him home again.

Once home, he distracted himself with the desire to become a king, and in the midst of a political campaign, he was struck into silence, becoming at the end of his waiting—as he would put it—an invisible person. He returned to Orun, not as a king, but, with Osun’s blessing, as one of the signal artists of the twentieth century.

Ulli Beier wrote that Twins Seven-Seven’s great creation was himself. His triumph was that he lived life to the limit. Bravely taking on new tasks, winning, then losing, then winning again, Prince looked forward and went forward, remaining perpetually in motion. But what will last is the art that incarnates, permanently, his talent and intentions.

Prince’s art was grounded in an inherent talent that unified imagination and skill. They met so easily—imagination and skill, thought and action—that the choice of an artist’s head in Obatala’s garden is as good an explanation as any. Born an artist, he rarely paused for a thought, his hand kept going. Planning was minimal, the end uncertain: he started with wide, swift gestures, confirmed them with black outlines, then filled bold forms with delicate, geometric patterning, proceeding in an additive process that he called ant work, that Robert Plant Armstrong called syndesis and identified forty years ago as the key feature of Yoruba creation. Prince rolled the Yoruba aesthetic onto a flat European surface, creating paintings that matched the masterworks of Western modernism.

Not from influence, but through parallels of proclivity, Prince’s works resemble Paul Klee’s. Both were musicians, both were draftsmen who rendered the invisible with precision. Prince’s paintings, like Pollock’s dripped pictures, develop order through tonal balance, establish connections through curving lines, and achieve depth out of variations in scale.

Prince’s bright, particular talent unfolded in a fraught historical context. He was born in a British colony, and in early anger he felt that, as he put it, the British had come with their guns and books to destroy his civilization. Educated in Islamic and Christian schools, he turned away from the intrusive new faiths of his parents to embrace the rooted religion of the Yoruba people. His radical, oppositional stance positioned him among the artists who, in the moment of Nigerian independence, set about the creation of a culture that drew ideas from the West but sought for its energy in the native tradition. The writers led, but Prince was there. He read Amos Tutuola’s novels, he acted in plays by Wole Soyinka, and, like them, he employed alien media to bring the Yoruba tradition into new vitality.

Opposition to external intrusion and internal decay, awareness of international developments, and the selective retrieval of old traditions combined in innovative actions to shape and propel the force of modernism. Like Yeats in poetry or Bartók in music, Prince, the painter, was a modernist.

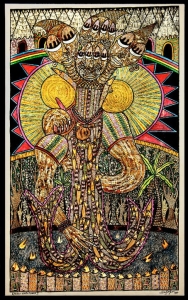

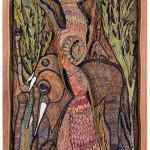

At once personal and traditional, oppositional, innovative, and modern, Prince’s works assemble into an exhibition of his worldview. He painted scenes of village life that erased all signs of colonial presence to imagine a unity of labor and faith. His village scenes stood against the decadent fragmentation of contemporary existence. Inspired by the folk fables his mother told, he used animals to expose moral problems. His pictures of animals argue for critical self-awareness. Most often he pictured the Yoruba spirits and deities, revealing the unseen powers of the universe to affirm his commitment to the old Yoruba faith. As Prince’s life wore on, his prime subject became the goddess Osun; her image, an icon, was for him a prayer to his goddess.

Prince’s oeuvre contains many self-portraits. Unlike Rembrandt’s, these do not record his physical appearance. They make visible his inner state and external conditions, symbolizing in sequence the changes in his life. In an early masterpiece, The Dream of the Abiku Child, painted in 1967, a child with the slit eyelids of a spirit—empowered to see into both worlds—rises to the stars from a dark river, rich with golden fish. The fish are the devotees of Osun who swarm to give her form. The picture shows an abiku child rescued from death and protected in life by the goddess of fertility. Lifting from the darkness, this is Prince at birth.

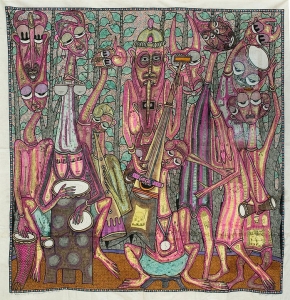

One of Prince’s last masterpieces, The Spirits of My Reincarnation Brothers and Sisters, was painted in Philadelphia during the winter of 2006–2007. He had used a similar title for a painting made late in the 1960s, which is now in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. It pictured his deceased brothers and sisters as spirits, Alokolobo on the left, Sigidi on the right. They reappear in the new painting, but now they are musicians, and the leader of their band stands centrally among them. They sway and twist, peering through lidded and split spirit eyes. Their leader stands firmly on the midline; his eyes are the sad eyes of a human being. The leader is Prince. The spirits represent the people around him who hound him for money, who rely on him for leadership, but burden him with incessant demands. Successful and sad, this is Prince at the end.

Prince Twins Seven-Seven was a complicated man who led a complicated life, and he was a friend of mine. The man was a wonder, his dreams spread as wide as the sky. Beginning, in his words, as “a throwaway boy from the bush,” what he accomplished is astounding. He might have been a king; he was a great artist. The works he left us recall an exhilarating moment in the history of art, before the postmodern collapse into the trivially familiar, and they will endure, preserving the spirit of a skilled, imaginative man who laughed easily and wept, courageously carrying on.

Henry Glassie is College Professor Emeritus at Indiana University, and the author of numerous books, including Passing the Time in Ballymenone (1982), Turkish Traditional Art Today (1993), Art and Life in Bangladesh (1997), Material Culture (1999), Vernacular Architecture (2000), and Prince Twins Seven-Seven (2010). He has received many awards for his work, most recently the award for a lifetime of scholarly achievement from the American Folklore Society and the Charles Homer Haskins Prize of the American Council of Learned Societies for a distinguished career of humanistic scholarship.