Material Culture is proud to announce its next special exhibition, “5 Vermont Artists: Sculpture and Assemblages” which will open on June 30, 2012, and run through July 30. These five talented artists are bound not only by geography, but by a shared communication with natural materials or found objects, and an ability to transform their media into the creation of new, compelling universes. A reception on June 30, from noon to five, will mark the commencement of the exhibition, with two of the artists, Larry Simons and Abby Rieser, present.

Artwork by Paul Bowen.

Paul Bowen is known for his earthy, muscular works of found wood and metal. Born in 1951 in Wales, he entered art school there in 1968 and graduated four years later with a degree in Art and Design, working, as he says, “in the space between painting and sculpture.” His further studies brought him to the Maryland Institute, where his love for abstract expressionism deepened in his work with Grace Hartigan, Ed Dugmore and Sal Scarpitta and his exploration of the New York art scene. It was his move back to the U.K., however, to take a post in the department of sculpture at Sheffield Polytechnic, that pushed him fully into the world of sculpture. He received the Welsh Arts Council Award to Artists, and his, by now, truly impressive list of exhibitions had been started with showings in Wales, Scotland and Italy. The work that might now be considered his signature, though, resulted from several fellowships from the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Massachusetts. Scouring the beaches of Cape Cod, he found wood, both natural and post-consumer, that he joined together to create pieces that are sometimes imposing, sometimes aerially light. An exhibition in New York in 1983 soon led to frequent showings in the United States, and by this time, Bowen says, the influences of his work “were clearly less my Welsh background and more waterfront structures, boats, the Cape Cod light…and particularly the marine mirages, called ‘the looming,’ often seen here in the winter.” Circles and curves tend to dominate straight lines in Bowen’s abstract work, drawing the power of the worn wood into their encompassing, sometimes massive, forms. Rougher forms often inhabit the circle, or sticks may spill from a barrel, as seen at right, in a gesture evocative of both water or sea life. The silhouette of a fishing boat called a “dragger” recurs in another interplay between abstract and figurative form. In addition to countless exhibitions, Bowen’s work appears in the permanent collections of the Guggenheim in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Fogg Art Museum in Cambridge, MA, the Association of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Ghent, Belgium, and a dozen other esteemed art museums in the United States and Britain.

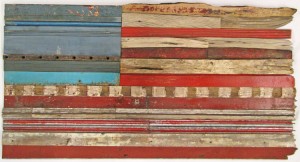

Flag by Larry Simons.

Larry Simons, who lives in a house he designed and built himself on forty-two acres near Brattleboro, Vermont, also specializes in assemblages of found wood and metal objects. The wood Simons uses is both natural, such as driftwood, or pre-rendered from its previous life as part of a building, tool, piece of furniture, or other consumer object. He created his first sculptures in 1965, from the leather scraps from a sandal shop where he worked on Cape Cod. In his work since, he describes himself as a “recycler by nature,” saying, “virtually everything I use in my art has had a previous life – bobbins, chair spindles, tool handles, toys, croquet sets and wooden patterns from steel mills,” for example. Moved by weathered buildings, Simons’ work takes on the rusticity he loves, and the compositions, whether symmetrical or irregular, showcase the lines of objects evocative of the past. The metal that appears in his pieces is frequently rusted, as he appreciates the hue of rust in conjunction with that of wood, and it serves further to endow his objects with a sense of age. He prefers to work with the colors of objects he finds, rather than repainting or recoloring anything, so his creation of an assemblage such as the flag, at left, require tracking down pieces of the necessary red, white, or blue. Much of Simons’ work, like the flag, lines up or stripes the different pieces of wood, creating a tension between the rigidity of the vertical or the horizontal, and the irregularity of the found objects.

Sculpture by Abigail Rieser

Abigail Rieser masterfully uncovers the beauty of found objects in her assemblages. The objects she sources are extremely diverse, though a theme of time-worn surfaces occurs throughout. Her assemblages also vary widely in shape, texture, and emotionality; round balls of different shapes and sizes play against straight lines, grids and spirals; wheels with solar spikes are part of sharp machines; some frames seem like traps for their abstract subjects, while clear figures such as birds, horses, or a man on a tractor happily inhabit the structures of others. Rieser trained in metalwork, sculpture and two-dimensional design beginning in her teens at the Putney School; afterwards, she enrolled in a course at Penland School of Crafts to continue her work in metal and jewelry design. From 1978 to 1982 she attended the Rhode Island School of design, focusing on metalwork and surface design on textiles. Her fascination with all of these varying textures, and her true craftsmanship in fusing them into single pieces, gives her sculpture’s forms a compelling and dynamic physics.

“Pocketed Investments,” by B.Z. Reily.

B.Z. Reily, another artist working with found material, describes her sources as “weathered and worn objects, antique wood, metal scraps, Raku clay, bits and pieces from the natural world, and remains from our consumer culture.” Her past work has often regrouped her various discovered objects into figures and recognizable forms, rather than the chiefly abstract work of artists such as Simons or Bowen. Reily’s works, from faces which she titles “Masks,” to animals such as flies made of metal scraps, to figures reminiscent of human forms, take on a spirit that is greater than the sum, or even juxtaposition, of its parts. More recently, she has turned to the task of creating “Quilts,” though rather than piecing together fabric, she applies this traditional quilting practice to metal, wood, clay, or objects like old board games or baseball gloves. One of these quilts, “Pocketed Investments,” for example, consists of a base made of blue jean fragments, overlaid with items that Reily found by asking friends and relatives to turn out the contents of their pockets. Foreign coins, guitar picks, matchbooks and keys dance in rows on the map of denim, a background reminiscent of their origin. The entire pieces arrest the viewer with their similarity to stitched or woven quilts, and upon further examination, one is rewarded by recognition of the unexpected but familiar objects that make up the whole.

Mark Fenwick rounds out the group of five, whose fantastical wood sculptures are carved rather than ‘assembled,’ and he is as likely to chop his lumber down himself than collect fallen branches. As a child in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, he enjoyed splitting firewood, and when he moved to an artist commune with friends in his teenage years, he spent most of his time outdoors felling trees for use on their farm. This collection of artists and writers near Brattleboro, Vermont, also staged magnificent productions for the community each summer as the Monteverdi Players, and here Fenwick was able to apply his skill at wood-carving, an art he began as a child with pieces from the wood pile. Like the gigantic creations which formed stage sets or pieces for these plays, much of Fenwick’s work is life-sized or larger, drawing the viewer into immediate relation to the figures, human or animal, or strange woodland faces that emerge from inanimate forms. Some of his work is abstract, and from some, clear figures emerge, but all of them are suffused with mystery, fusing a recognizable element such as a foot or a bird to more abstract shapes. Some, like a man in a flying boat or a bull with a man’s body and a fish’s tail, seem like the subjects of myth; some have religious resonance, such as an abstract Buddha bearing a feather; other collections of human figures or structures seem the stuff of dreams. Fenwick is currently at work restoring an inventive home he built—called “The Castle” by the local community—in his earlier days at the artists’ commune. Years of exploration led him away, but he has returned to this inhabitable sculpture in Vermont, populating it with his sculptures.