FINE ANTIQUE RUGS AND TEXTILE ARTS

Featuring the John T. Wertime Collection with Other Fine Estates and Private Collections

2-Day Live Showroom Auction: June 17-18, 2024, 11AM ET

DAY 1: RUGS, KILIMS, TRAPPINGS (LOTS 1 – 410)

Live Showroom Auction: Monday, June 17, 11AM ET

DAY 2: TEXTILE ARTS (LOTS 411 – 639)

Live Showroom Auction: Tuesday, June 18, 11AM ET

Exhibition: June 14-15-16, 11AM-4PM

Join Us! Exhibition Reception and Refreshments, Sunday, June 16, Noon to 4PM

Special 2PM Gallery Walk Through & Discussion:

James Opie (author of Tribal Rugs: Nomadic and Village Weavings from the Near East and Central Asia)

and Material Culture founder, George Jevremovic

Philadelphia, PA., June, 2024 — Twenty-six years ago, John Wertime’s article featuring a portion of his extensive collection appeared in HALI, “Back to Basics: Primitive Pile Rugs of West & Central Asia.” While focused on structural characteristics and technique, the visuals captured their readers. That article featured chosen examples from Anatolia east through Persia, Afghanistan, and Central Asia, only a small segment of his expansive collection featured in our auction.

Beginning with the minimalist art that so fascinated John Wertime, the appeal is immediately apparent; the grouping of his material in the initial lots offers deep insights into the weavers’ mindset. The group exudes a presence that speaks not only to our eyes but to our souls as well. The auction begins with a rather unusual Shahsevan bag (lot 1) – a design executed in natural brown wool and an undyed, unbleached ivory ground. More commonly thought of as a source for colorful flat-woven kilims and bags, in stark contrast, the undyed fiber of natural brown and white contributes to a rare and visually powerful composition. Similarly, the Siirt area “mohair” kilims (lot 2) represent an exercise in natural wool used to great advantage. Though made with pile, referring to them as kilims is accurate. Rather than knotted, the pile-like effect is the result of combing out the warps of natural brown and cream-colored wool to create the appearance and feel of a pile rug. The technique is likely centuries older than these examples from the Wertime Collection, but the result is likely quite similar to what tribeswomen in the borderlands of southeast Anatolia and Persia made in the distant past.

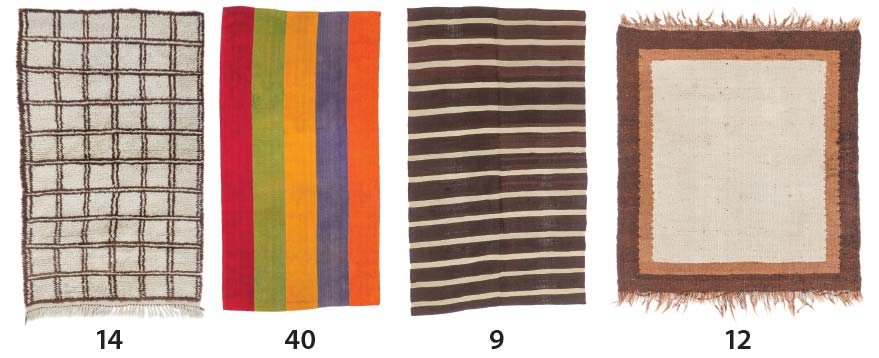

The presentation continues with ‘Tulu’ rugs (long pile sleeping rugs, lot 14) from elsewhere in central Anatolia, woven with a pile looping technique more familiar to collectors of traditional rugs and the less well-known cirpi/kilims (lot 40) also with completely saturated colors applied to brilliant, lustrous wool. Also included are equally minimalist in terms of color true flat weaves, including Shahsevan striped kilims (lot 9), and an unusually plain west Persian sofreh kilim of all natural, undyed wool too (lot 12).

The presentation continues with ‘Tulu’ rugs (long pile sleeping rugs, lot 14) from elsewhere in central Anatolia, woven with a pile looping technique more familiar to collectors of traditional rugs and the less well-known cirpi/kilims (lot 40) also with completely saturated colors applied to brilliant, lustrous wool. Also included are equally minimalist in terms of color true flat weaves, including Shahsevan striped kilims (lot 9), and an unusually plain west Persian sofreh kilim of all natural, undyed wool too (lot 12).

Minimalism as a decorative characteristic is especially soothing to the eyes, and Wertime’s fascination with this angle on collecting stands in stark contrast to his other work in the field with Persian tribal bags (especially sumacs with elaborately intricate designs with saturated colors) coupled with a love for (if not extensive experience with) rugs and textiles from Central Asia. An unusually graphic ‘jajim’ or flat woven cover attributed to the Uzbeks stands alone here (lot 49). Composed of vertical interlocking rows of primary colors, including red, indigo blue, lemon yellow, a deep-sea blue/green, and apparently a natural white wool, the composition resembles more a Rastafarian textile from Jamaica than a Central Asian cover. Curiously included in the minimalism is an intricately patterned Anatolian çicim with repeating rams horn (or kotchanak devices with rams horns top and bottom, a fertility symbol, lot 61) in white on a subtly dyed madder red ground. The supplementary technique of applying the design to the red ground is another structural type that Wertime found interesting. A stickler for structure, this aspect of his approach to collecting is out of the casual reach of most collectors, as well as dealers too.

Minimalism as a decorative characteristic is especially soothing to the eyes, and Wertime’s fascination with this angle on collecting stands in stark contrast to his other work in the field with Persian tribal bags (especially sumacs with elaborately intricate designs with saturated colors) coupled with a love for (if not extensive experience with) rugs and textiles from Central Asia. An unusually graphic ‘jajim’ or flat woven cover attributed to the Uzbeks stands alone here (lot 49). Composed of vertical interlocking rows of primary colors, including red, indigo blue, lemon yellow, a deep-sea blue/green, and apparently a natural white wool, the composition resembles more a Rastafarian textile from Jamaica than a Central Asian cover. Curiously included in the minimalism is an intricately patterned Anatolian çicim with repeating rams horn (or kotchanak devices with rams horns top and bottom, a fertility symbol, lot 61) in white on a subtly dyed madder red ground. The supplementary technique of applying the design to the red ground is another structural type that Wertime found interesting. A stickler for structure, this aspect of his approach to collecting is out of the casual reach of most collectors, as well as dealers too.

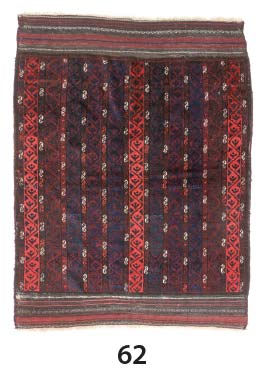

The Wertime Collection offerings conclude with a very atypically designed lot 62, a Baluch rug from Northeast Persia with vertical stripes containing unusual repeating motifs resembling a plant. With no border systems enclosing the field design, the minimalist aspect of design accentuated by the limited range of color is apparent. Wertime was one of the very few western dealers who lived ‘in situ’ for some years and was fluent in any of the spoken languages – in his case, Persian. His language skills translated directly to his ability to think ‘with’ some of the women responsible for producing some of the rugs and textiles in this auction or, at the very least, allowed him greater sensitivity and insights that few of us in the West could ever imagine and likely will never fully understand.

The Wertime Collection offerings conclude with a very atypically designed lot 62, a Baluch rug from Northeast Persia with vertical stripes containing unusual repeating motifs resembling a plant. With no border systems enclosing the field design, the minimalist aspect of design accentuated by the limited range of color is apparent. Wertime was one of the very few western dealers who lived ‘in situ’ for some years and was fluent in any of the spoken languages – in his case, Persian. His language skills translated directly to his ability to think ‘with’ some of the women responsible for producing some of the rugs and textiles in this auction or, at the very least, allowed him greater sensitivity and insights that few of us in the West could ever imagine and likely will never fully understand.

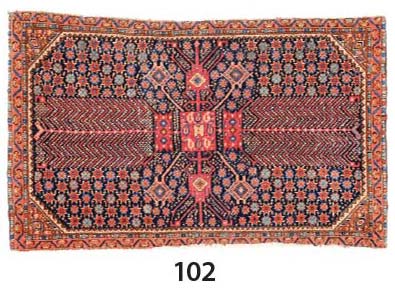

The auction continues in a similar vein with equally minimalist, sparsely ornamented weavings that, if Wertime were alive today, he very well might have been the most active client. Striped jajims from Persia, specifically the Mazandaran area, are subsequently featured, a group only recently “discovered” by European dealers able to visit Iran. The next group of weavings includes colorful tribal rugs and bags from Persia, with an outstanding Afshar bag face (lot 102). Unusual in every way, a similar example appears in Rothberg’s book “Nomadic Visions” (plate 126). Clearly a ‘design type,’ it is one that is rarely seen. Others of note include a very elaborately patterned Ferahan Sarouk prayer rug, an exceptional weaving featuring animal life with vegetation evocative of the classical Persian rug design pool – confronting birds peering back over their shoulders astride a pot of meandering vines and flowers coupled with conical shaped cypress trees reminiscent of Baktiari drawing.

The auction continues in a similar vein with equally minimalist, sparsely ornamented weavings that, if Wertime were alive today, he very well might have been the most active client. Striped jajims from Persia, specifically the Mazandaran area, are subsequently featured, a group only recently “discovered” by European dealers able to visit Iran. The next group of weavings includes colorful tribal rugs and bags from Persia, with an outstanding Afshar bag face (lot 102). Unusual in every way, a similar example appears in Rothberg’s book “Nomadic Visions” (plate 126). Clearly a ‘design type,’ it is one that is rarely seen. Others of note include a very elaborately patterned Ferahan Sarouk prayer rug, an exceptional weaving featuring animal life with vegetation evocative of the classical Persian rug design pool – confronting birds peering back over their shoulders astride a pot of meandering vines and flowers coupled with conical shaped cypress trees reminiscent of Baktiari drawing.

A group of Caucasian rugs follows, along with another collection of Turkish rugs and bags. A Talish rug (lot 138) stands apart from many of the other Caucasian rugs. Without an empty field, the colorful varied motifs are sharply contrasted against a dark indigo blue field. An extremely unusual Seichur rug (lot 153), while not the oldest rug in the world (but who’s counting), is exceptionally dazzling, with both the field and border shimmering with colorful, small pattern filler motifs resembling shards of stained glass reflecting rays of sunlight.

A group of Caucasian rugs follows, along with another collection of Turkish rugs and bags. A Talish rug (lot 138) stands apart from many of the other Caucasian rugs. Without an empty field, the colorful varied motifs are sharply contrasted against a dark indigo blue field. An extremely unusual Seichur rug (lot 153), while not the oldest rug in the world (but who’s counting), is exceptionally dazzling, with both the field and border shimmering with colorful, small pattern filler motifs resembling shards of stained glass reflecting rays of sunlight.

The listings of Turkish rugs commence with an early Konya area yastik (lot 158) and an equally old rug from the same region (lot 161). But a rug or runner type weaving (?), lot 167, though not as old, is as memorable as any we have handled over the years. The archaic totemic design on the classic Konya yellow field is unlike anything else on offer in this sale as the simple and extremely graphic patterning might tempt some to date it earlier than cataloged. A colorful Dazkiri rug (lot 170) from southwest Anatolia concludes this section of the sale. The colorful and classically drawn talismans floating on the red ground resemble, for want of an immediate analogy in wool, the silver pendants seen with many of the Turkmen tribal groups. Triangular in shape with three strands from which another triangular shaped pendant hangs, the relationship to a related design pool from further east in Central Asia is unmistakable. Complete with the occasional water flask and boldly drawn fertility symbols, the breadth and depth of cultural connection is successfully communicated.

The listings of Turkish rugs commence with an early Konya area yastik (lot 158) and an equally old rug from the same region (lot 161). But a rug or runner type weaving (?), lot 167, though not as old, is as memorable as any we have handled over the years. The archaic totemic design on the classic Konya yellow field is unlike anything else on offer in this sale as the simple and extremely graphic patterning might tempt some to date it earlier than cataloged. A colorful Dazkiri rug (lot 170) from southwest Anatolia concludes this section of the sale. The colorful and classically drawn talismans floating on the red ground resemble, for want of an immediate analogy in wool, the silver pendants seen with many of the Turkmen tribal groups. Triangular in shape with three strands from which another triangular shaped pendant hangs, the relationship to a related design pool from further east in Central Asia is unmistakable. Complete with the occasional water flask and boldly drawn fertility symbols, the breadth and depth of cultural connection is successfully communicated.

A small group of Baluch weavings is next, punctuated by an unusually colorful, graphically interesting design on an ivory field (lot 175), possibly from the Ferdauz area of NE Persia. With a flowering tree emerging from a pot at the bottom of the field, this design type is normally found on a camel-colored ground of a limited palette. But in this rug, we find a clear iridescent medium blue, a true lemon yellow, and an unusually clear madder red. The border is spaciously drawn, unusually so, as the weaver left room to develop her version of a meandering vine with flower border, a type seen on classic rugs from weaving centers elsewhere in NW Persia. Chosen by a respected panel who curated a 1998 exhibition from Canadian collections, it is no wonder it is perhaps the most unusual Baluch example in this sale. Not to be discounted though, lot 181, a Baluch octagon bag face, features everything that has characterized this design type as very desirable, one of which collectors apparently never tire.

A small group of Baluch weavings is next, punctuated by an unusually colorful, graphically interesting design on an ivory field (lot 175), possibly from the Ferdauz area of NE Persia. With a flowering tree emerging from a pot at the bottom of the field, this design type is normally found on a camel-colored ground of a limited palette. But in this rug, we find a clear iridescent medium blue, a true lemon yellow, and an unusually clear madder red. The border is spaciously drawn, unusually so, as the weaver left room to develop her version of a meandering vine with flower border, a type seen on classic rugs from weaving centers elsewhere in NW Persia. Chosen by a respected panel who curated a 1998 exhibition from Canadian collections, it is no wonder it is perhaps the most unusual Baluch example in this sale. Not to be discounted though, lot 181, a Baluch octagon bag face, features everything that has characterized this design type as very desirable, one of which collectors apparently never tire.

Turkmen rugs and bags are next on the auction agenda. An unusually nice Tekke six göl torba with a border design type that seems to date it to the first half of the 19th century features a tertiary device seldom seen in weavings of a type that tends to portray a very codified and standard aesthetic. The elem, too, is decorated – not the usual manner in which these torbas of shallow storage bags are finished. The small göl format chuval (lot 191) features the full flower forms favored by the Tekke in the elaborately decorated elem or bottom skirt panel of this larger storage bag – a feature that separates it from many. Thought to have been woven for dowry, such posh items were probably not intended for everyday use with most of the damage (missing edges/selvedge) incurred probably occurred in the West rather than in situ. The Tekke Kizil chuval format is one that many collectors understandably have overlooked, as most are late with obvious color run and more, but this example, lot 193, is an earlier example too.

Turkmen rugs and bags are next on the auction agenda. An unusually nice Tekke six göl torba with a border design type that seems to date it to the first half of the 19th century features a tertiary device seldom seen in weavings of a type that tends to portray a very codified and standard aesthetic. The elem, too, is decorated – not the usual manner in which these torbas of shallow storage bags are finished. The small göl format chuval (lot 191) features the full flower forms favored by the Tekke in the elaborately decorated elem or bottom skirt panel of this larger storage bag – a feature that separates it from many. Thought to have been woven for dowry, such posh items were probably not intended for everyday use with most of the damage (missing edges/selvedge) incurred probably occurred in the West rather than in situ. The Tekke Kizil chuval format is one that many collectors understandably have overlooked, as most are late with obvious color run and more, but this example, lot 193, is an earlier example too.

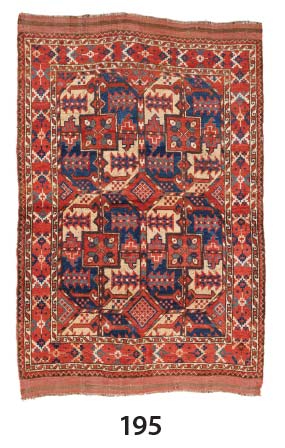

A Central Asian rug, Lot 195, is similar to that featured on the cover of “Rugs and Carpets from Central Asia” composed by Elena Tsareva (curator at the Russian Ethnographic Museum) in 1984. The interlocking göls or medallions in the field form a completely different medallion in the center, a visual trick successfully executed by the weaver. The border and palette suggest a middle Amu Darya provenance, and the weavers are likely non-Turkmen or Uzbek as cataloged. Turkmen weavers adhere much more closely to the classic design types without variation, never allowing for this striking composition.

A Central Asian rug, Lot 195, is similar to that featured on the cover of “Rugs and Carpets from Central Asia” composed by Elena Tsareva (curator at the Russian Ethnographic Museum) in 1984. The interlocking göls or medallions in the field form a completely different medallion in the center, a visual trick successfully executed by the weaver. The border and palette suggest a middle Amu Darya provenance, and the weavers are likely non-Turkmen or Uzbek as cataloged. Turkmen weavers adhere much more closely to the classic design types without variation, never allowing for this striking composition.

A thoughtfully chosen group of Shahsevan sumacs follows, with some obvious ones of merit including lot 212, a bag face with a white ground medallion dominating the field, followed by another with multi-colored classic double-headed Shahsevan birds arranged on a midnight blue field framed by a simple border, ex Ronnie Newman collection. Another once owned by that renowned dealer is an unusual pair of sumac bags (lot 217) – true pairs seldom appear in the marketplace – followed by a charming west Persian sumac bag with a large eight-pointed star on a field framed by a border consisting of an animal train of colorful beasts. An assortment of various tribal bag faces, including lot 231, a Khamseh pile bag face with a characteristic secondary motif, often found accenting a central primary medallion, in this example is drawn to form medallions adjacent to one another repeating throughout the field.

A thoughtfully chosen group of Shahsevan sumacs follows, with some obvious ones of merit including lot 212, a bag face with a white ground medallion dominating the field, followed by another with multi-colored classic double-headed Shahsevan birds arranged on a midnight blue field framed by a simple border, ex Ronnie Newman collection. Another once owned by that renowned dealer is an unusual pair of sumac bags (lot 217) – true pairs seldom appear in the marketplace – followed by a charming west Persian sumac bag with a large eight-pointed star on a field framed by a border consisting of an animal train of colorful beasts. An assortment of various tribal bag faces, including lot 231, a Khamseh pile bag face with a characteristic secondary motif, often found accenting a central primary medallion, in this example is drawn to form medallions adjacent to one another repeating throughout the field.

An even larger selection of old and admirable Anatolian kilims appears next in the listings. Two prayer kilims from East Anatolia, one firmly attributed to Erzerum, are noteworthy (lots 245, 246), with the latter including tree-like design elements certain to entertain and intrigue the eyes of most collectors already fascinated by this genre of weavings. Many of these kilims come from two collections – Alan Garrison and George Fine, an experienced collector/dealer who once organized a carpet conference gathering in Tucson, AZ and obviously spent considerable time in Istanbul as well. Both collections were assembled many years before, which explains the extraordinary condition in which many of the group appear.

An even larger selection of old and admirable Anatolian kilims appears next in the listings. Two prayer kilims from East Anatolia, one firmly attributed to Erzerum, are noteworthy (lots 245, 246), with the latter including tree-like design elements certain to entertain and intrigue the eyes of most collectors already fascinated by this genre of weavings. Many of these kilims come from two collections – Alan Garrison and George Fine, an experienced collector/dealer who once organized a carpet conference gathering in Tucson, AZ and obviously spent considerable time in Istanbul as well. Both collections were assembled many years before, which explains the extraordinary condition in which many of the group appear.

Garrison’s lot 253 is an unusually small weaving, possibly a Hotamis type of which very few of this diminutive size have been published. Sparsely ornamented with a clear palette and wonderful reciprocal trefoil border on either side suggest it could very well be older than the safely cataloged early 19th-century date offered. Most complete Anatolian kilims are rather unwieldy – long and difficult to properly display in most private homes but that is not the case here. The next lot, ex-George Fine Collection, again is dated to the early 19th century, though the animals flanking the central pole on the white field are drawn in the earliest style with a single head crowned with two horns and clearly defined body. Few early examples from southwest Anatolia (Fetiyeh region) are around, yet Fine collected two tentatively dated to circa 1800 or before, both with signs of wear. The damage notwithstanding, the overall impression is one of art, especially lot 257. But most collectors gravitate towards those flat weaves from central Anatolia and lot 264 has it all. Cataloged as circa 1800, few would ever doubt that date as it is the other half of a kilim featured in the McCoy Jones Collection of Anatolian kilims in the Fine Arts Museum in San Francisco, the ex-Gary Muse collection (plate 64) that first defined the parameters by which collectors first judged these weavings more than 30 years ago. Actually, a very small percentage of rug or kilim fragments appearing in the marketplace are ever called “important,” but Anatolian kilims of significant age, fragmented or otherwise, are more often than not regarded as just that, and lot 264 is one of them. The pink hue red dye is an older dye evident in only the older examples. Lot 268, another ex-Fine Collection entry, is an obviously ancient example. The horizontal lines of patterning speak loudly of a long-past era of design. Woven in two pieces, the motifs radiate from the center in either direction, mirror images and all the more dazzling as well as interesting when the colors used are reversed with, for example, green as the ground for a simple element woven in red and vice versa on the opposing half. Some of these artistic touches might be considered unremarkable but do indicate a mindful intent to playfully entertain the eye, not only ours at this late date in time but their own as well.

Garrison’s lot 253 is an unusually small weaving, possibly a Hotamis type of which very few of this diminutive size have been published. Sparsely ornamented with a clear palette and wonderful reciprocal trefoil border on either side suggest it could very well be older than the safely cataloged early 19th-century date offered. Most complete Anatolian kilims are rather unwieldy – long and difficult to properly display in most private homes but that is not the case here. The next lot, ex-George Fine Collection, again is dated to the early 19th century, though the animals flanking the central pole on the white field are drawn in the earliest style with a single head crowned with two horns and clearly defined body. Few early examples from southwest Anatolia (Fetiyeh region) are around, yet Fine collected two tentatively dated to circa 1800 or before, both with signs of wear. The damage notwithstanding, the overall impression is one of art, especially lot 257. But most collectors gravitate towards those flat weaves from central Anatolia and lot 264 has it all. Cataloged as circa 1800, few would ever doubt that date as it is the other half of a kilim featured in the McCoy Jones Collection of Anatolian kilims in the Fine Arts Museum in San Francisco, the ex-Gary Muse collection (plate 64) that first defined the parameters by which collectors first judged these weavings more than 30 years ago. Actually, a very small percentage of rug or kilim fragments appearing in the marketplace are ever called “important,” but Anatolian kilims of significant age, fragmented or otherwise, are more often than not regarded as just that, and lot 264 is one of them. The pink hue red dye is an older dye evident in only the older examples. Lot 268, another ex-Fine Collection entry, is an obviously ancient example. The horizontal lines of patterning speak loudly of a long-past era of design. Woven in two pieces, the motifs radiate from the center in either direction, mirror images and all the more dazzling as well as interesting when the colors used are reversed with, for example, green as the ground for a simple element woven in red and vice versa on the opposing half. Some of these artistic touches might be considered unremarkable but do indicate a mindful intent to playfully entertain the eye, not only ours at this late date in time but their own as well.

The wealth and breadth of design with which the weavers of Anatolia felt comfortable is actually quite amazing. From a simple banded design with repeating elements (lot 280), to the colorful complexity of interlocking motif (lot 263) to the strikingly archaic saf design of colorful contiguous arches repeating throughout its length, the art of Anatolia is one with which anyone should feel privileged to live. Even those believed to be later, i.e., circa 1875 (lots, 296 – 298, 310,) retain singular characteristics that define the art of Anatolia from that of other weaving areas around the world.

The wealth and breadth of design with which the weavers of Anatolia felt comfortable is actually quite amazing. From a simple banded design with repeating elements (lot 280), to the colorful complexity of interlocking motif (lot 263) to the strikingly archaic saf design of colorful contiguous arches repeating throughout its length, the art of Anatolia is one with which anyone should feel privileged to live. Even those believed to be later, i.e., circa 1875 (lots, 296 – 298, 310,) retain singular characteristics that define the art of Anatolia from that of other weaving areas around the world.

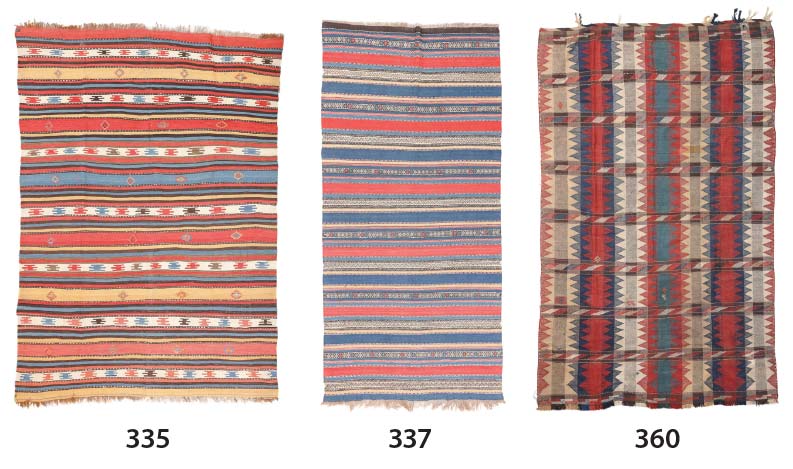

Kilims from the neighboring region of NW Persia, home to Shahsevan weavers whose kilims, while not with the colorful magic of Anatolian examples, are quite lovely in their own right. Lots 335 and 337 incorporate the sublime palette seen in Anatolia, a visually pleasing and successful composition of broader and narrower stripes of clear, uncompromised color. The indigo blue, madder red, and yellow dyestuffs are undoubtedly of the very best quality. A few Qashqai kilims complete this eye-dazzling display of textile art, introduced with a Mowj example, a twill type weaving occasionally made by the Qashqai (lot 360), followed by a flat weave that would have been called “gabbeh” if it were a pile rug with blocks of primary color, compartments in a grid defined by notched vertical and horizontal lines of undyed ivory wool.

Kilims from the neighboring region of NW Persia, home to Shahsevan weavers whose kilims, while not with the colorful magic of Anatolian examples, are quite lovely in their own right. Lots 335 and 337 incorporate the sublime palette seen in Anatolia, a visually pleasing and successful composition of broader and narrower stripes of clear, uncompromised color. The indigo blue, madder red, and yellow dyestuffs are undoubtedly of the very best quality. A few Qashqai kilims complete this eye-dazzling display of textile art, introduced with a Mowj example, a twill type weaving occasionally made by the Qashqai (lot 360), followed by a flat weave that would have been called “gabbeh” if it were a pile rug with blocks of primary color, compartments in a grid defined by notched vertical and horizontal lines of undyed ivory wool.

Smaller rugs from Tibet and China follow, with enduring appeal to those already fascinated with the allure of the high plateau region and mysteries of the inscrutable East. The remaining pieces from the renowned Robert Piccus Collection complete the listings with a few outstanding examples. A crossed vajra / double dorje mat (lot 384) made in the enigmatic so-called “Wangden” technique, a legacy that some believe represent a style of weaving that predates the more standard manner in which most Tibetan rugs are woven, an archaic method used nowhere else. But the most beautiful Tibetan example on offer may be lot 376. Beautifully dyed with an unfailingly saturated indigo blue ground shade with no abrash, the other dyes are exceptionally clear and saturated as well. Both lots 367 and 368 are old and admirable examples of Ningxia weaving, while the seating mat from Gansu, lot 375 – ex Robert Piccus Collection- is extremely interesting, framed by a tie-dyed tigma pattern more commonly seen in a flat woven wool cloth than this pile rendition. Though dated to circa 1920, it is clearly unusual as few equally nice and similarly patterned examples have been published. Another Piccus rug, lot 383, is an oddly graphic weaving, possibly a pillar rug, with the head/face of an unidentifiable mythical beast floating above a rounded (possibly a throne?) rug – all suspended among clouds above the classic mountain/wave bottom end finish design. Hardly the oldest example extant, it is of undeniable interest and intrigue as analogous examples do not immediately come to mind.

Smaller rugs from Tibet and China follow, with enduring appeal to those already fascinated with the allure of the high plateau region and mysteries of the inscrutable East. The remaining pieces from the renowned Robert Piccus Collection complete the listings with a few outstanding examples. A crossed vajra / double dorje mat (lot 384) made in the enigmatic so-called “Wangden” technique, a legacy that some believe represent a style of weaving that predates the more standard manner in which most Tibetan rugs are woven, an archaic method used nowhere else. But the most beautiful Tibetan example on offer may be lot 376. Beautifully dyed with an unfailingly saturated indigo blue ground shade with no abrash, the other dyes are exceptionally clear and saturated as well. Both lots 367 and 368 are old and admirable examples of Ningxia weaving, while the seating mat from Gansu, lot 375 – ex Robert Piccus Collection- is extremely interesting, framed by a tie-dyed tigma pattern more commonly seen in a flat woven wool cloth than this pile rendition. Though dated to circa 1920, it is clearly unusual as few equally nice and similarly patterned examples have been published. Another Piccus rug, lot 383, is an oddly graphic weaving, possibly a pillar rug, with the head/face of an unidentifiable mythical beast floating above a rounded (possibly a throne?) rug – all suspended among clouds above the classic mountain/wave bottom end finish design. Hardly the oldest example extant, it is of undeniable interest and intrigue as analogous examples do not immediately come to mind.

Day 2:

Day 2 is no less exciting as some colorful, graphic, and interesting examples of true textile art will be on offer, again presented in coherent groupings. It begins with a slew of ikats – complete ‘panels’ consisting of anything between four and six widths of woven silk ikat lengths sewn together to form these hangings often used as partitions or merely wall decoration in the traditional Uzbek’s home. Lots 416 and 419 might be considered the ‘stars’ of this group of nine, but all are in good condition with strong primary colors and designs of great visual impact. And for those with limited space who want merely an example of strong textile art on the wall to complement their decor, lot 432 consists of three well-chosen framed smaller ikat fragments from Central Asia.

Day 2 is no less exciting as some colorful, graphic, and interesting examples of true textile art will be on offer, again presented in coherent groupings. It begins with a slew of ikats – complete ‘panels’ consisting of anything between four and six widths of woven silk ikat lengths sewn together to form these hangings often used as partitions or merely wall decoration in the traditional Uzbek’s home. Lots 416 and 419 might be considered the ‘stars’ of this group of nine, but all are in good condition with strong primary colors and designs of great visual impact. And for those with limited space who want merely an example of strong textile art on the wall to complement their decor, lot 432 consists of three well-chosen framed smaller ikat fragments from Central Asia.

The following lot (433) is actually a rare type of Central Asian embroidery. Cataloged here as Uzbek, it may be Turkmen (possibly Saryk) but no one really knows for sure. Still, the colors are wonderful. Embroidered Chinese jackets and robes follow, Qing Dynasty (1644 – 1911) examples, but most of this material dates to the latter period of their rule. Lots 441 and 442 are complete depictions of the distinctive Qing period dragons pose, with the former including a rank badge embroidered completely with metal thread – a phoenix flying amidst clouds above a churning body of water. For those with a taste for minority textiles from China, lot 458, a Yao Shaman’s Robe, will be satisfying, complete and in good condition as well, though it has clearly been used too – an authentic garment with a long history rather than airport art for the tourist trade. Another carefully chosen group of Japanese kimonos with provenance to the Douglas Dawson Gallery in Chicago can be seen (lots 470 – 479), a curated offering of varying design types that, as a singular presentation, covers many of the bases valued by collectors of this material.

The following lot (433) is actually a rare type of Central Asian embroidery. Cataloged here as Uzbek, it may be Turkmen (possibly Saryk) but no one really knows for sure. Still, the colors are wonderful. Embroidered Chinese jackets and robes follow, Qing Dynasty (1644 – 1911) examples, but most of this material dates to the latter period of their rule. Lots 441 and 442 are complete depictions of the distinctive Qing period dragons pose, with the former including a rank badge embroidered completely with metal thread – a phoenix flying amidst clouds above a churning body of water. For those with a taste for minority textiles from China, lot 458, a Yao Shaman’s Robe, will be satisfying, complete and in good condition as well, though it has clearly been used too – an authentic garment with a long history rather than airport art for the tourist trade. Another carefully chosen group of Japanese kimonos with provenance to the Douglas Dawson Gallery in Chicago can be seen (lots 470 – 479), a curated offering of varying design types that, as a singular presentation, covers many of the bases valued by collectors of this material.

Rare examples of Tibetan saddlery follow, probably attributable to nomadic groups on the plateau, a type in which fewer traditional collectors of this type of material are interested as they have little to do with the monastic culture. They actually look like pieces that, if John Wertime were still alive, he would have bought them long ago as the minimalist/modernist appeal is obvious. Some made from natural, undyed yak hair from the Piccus Collection (lots 482, 491) and others with a simple ‘tigma’ or cross pattern stamped or dyed onto otherwise plain woven cream-colored wool, are from the true hinterlands of the plateau, types of which seldom are offered for sale in the West.

Rare examples of Tibetan saddlery follow, probably attributable to nomadic groups on the plateau, a type in which fewer traditional collectors of this type of material are interested as they have little to do with the monastic culture. They actually look like pieces that, if John Wertime were still alive, he would have bought them long ago as the minimalist/modernist appeal is obvious. Some made from natural, undyed yak hair from the Piccus Collection (lots 482, 491) and others with a simple ‘tigma’ or cross pattern stamped or dyed onto otherwise plain woven cream-colored wool, are from the true hinterlands of the plateau, types of which seldom are offered for sale in the West.

Ranging from Ottoman embroidery (lots 507 – 510) to the Zanskar coats of the Himalayan foothills (lots 512 – 513), a fine silk-embroidered textile from Sindh Province (Pakistan) is a highlight impossible to overlook (lot 514). In good condition with a simple pattern of embroidered circles randomly arranged on a field with borders top and bottom, it is a complete picture of hypnotic appeal accentuated by the free-hand drawing throughout – undoubtedly a rare example of textile art from the Indian subcontinent. In contrast to that finery, a strong image from the Rajasthan desert groups follows (lot 523), an antique tie-dyed shawl with a large-scale zig-zag pattern with incredibly fine detailing within the bold swaths of color.

Ranging from Ottoman embroidery (lots 507 – 510) to the Zanskar coats of the Himalayan foothills (lots 512 – 513), a fine silk-embroidered textile from Sindh Province (Pakistan) is a highlight impossible to overlook (lot 514). In good condition with a simple pattern of embroidered circles randomly arranged on a field with borders top and bottom, it is a complete picture of hypnotic appeal accentuated by the free-hand drawing throughout – undoubtedly a rare example of textile art from the Indian subcontinent. In contrast to that finery, a strong image from the Rajasthan desert groups follows (lot 523), an antique tie-dyed shawl with a large-scale zig-zag pattern with incredibly fine detailing within the bold swaths of color.

From India to Indonesia, lot 533 – an antique tie-dye silk panel from Lawon, stands apart from the other finely detailed offerings, featuring a Rothko-like image of a sea blue/green panel framed by a deep crimson red border. These textiles have been offered by dealers at shows and galleries for some time now, but the visual appeal never loses its luster. Unsurprisingly, the Dawson Gallery provenance catches the eye again with lots 553 – 583, spanning the African continent from the Congo and Zaire to West Africa. The Ewe Kente textiles, especially lots 559 and 560, are exceptionally colorful and again hypnotic eye dazzlers.

From India to Indonesia, lot 533 – an antique tie-dye silk panel from Lawon, stands apart from the other finely detailed offerings, featuring a Rothko-like image of a sea blue/green panel framed by a deep crimson red border. These textiles have been offered by dealers at shows and galleries for some time now, but the visual appeal never loses its luster. Unsurprisingly, the Dawson Gallery provenance catches the eye again with lots 553 – 583, spanning the African continent from the Congo and Zaire to West Africa. The Ewe Kente textiles, especially lots 559 and 560, are exceptionally colorful and again hypnotic eye dazzlers.

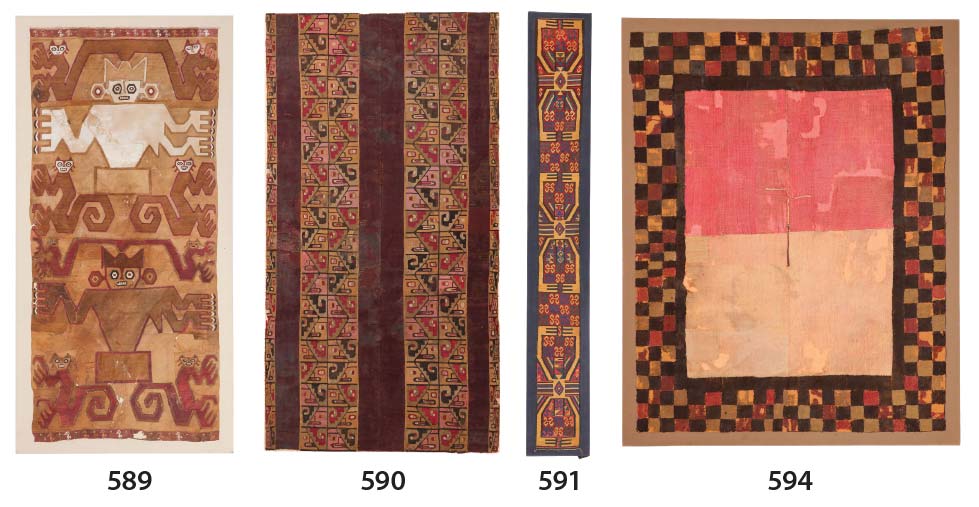

Completing the sale with historically significant textiles from the New World – pre-Columbian material from as early as 100 CE and the vibrant art of the Sihuas and Nazca cultures of the Peruvian south coast. Lot 591 is a complete panel in good condition and visually intriguing art. The Imperial Wari culture, too, is represented here with a largely complete tunic featuring fresh and vibrant colors that reveal the splendor of the weaver’s creative imagination and art in a garment intended for the elite members of their advanced civilization (lot 590). A minimalist Rothko-like Nazca culture tunic (lot 594) further exemplifies the relationship of truly antique textile art with a modern aesthetic. Although it was a garment to be worn, the visual appeal to our 21st-century sensibilities is undeniable and enduring – our eyes and minds never tire of this timeless composition of a tri-colored checkerboard framing the bold use of yellow and red (representing male/female aspects). The visual power of pre-Columbian textile art is not limited to the earliest period either. A large Chimu period tapestry (lot 589) probably once adorned a palace on the north coast of Peru, circa 1200 – 1500 CE. Again, the use of color apparently represents a metaphysical spiritual duality of the Andean belief system. The boldly rendered design on this largely intact and monumental example of textile art is an unusually powerful visual/artistic statement.

Completing the sale with historically significant textiles from the New World – pre-Columbian material from as early as 100 CE and the vibrant art of the Sihuas and Nazca cultures of the Peruvian south coast. Lot 591 is a complete panel in good condition and visually intriguing art. The Imperial Wari culture, too, is represented here with a largely complete tunic featuring fresh and vibrant colors that reveal the splendor of the weaver’s creative imagination and art in a garment intended for the elite members of their advanced civilization (lot 590). A minimalist Rothko-like Nazca culture tunic (lot 594) further exemplifies the relationship of truly antique textile art with a modern aesthetic. Although it was a garment to be worn, the visual appeal to our 21st-century sensibilities is undeniable and enduring – our eyes and minds never tire of this timeless composition of a tri-colored checkerboard framing the bold use of yellow and red (representing male/female aspects). The visual power of pre-Columbian textile art is not limited to the earliest period either. A large Chimu period tapestry (lot 589) probably once adorned a palace on the north coast of Peru, circa 1200 – 1500 CE. Again, the use of color apparently represents a metaphysical spiritual duality of the Andean belief system. The boldly rendered design on this largely intact and monumental example of textile art is an unusually powerful visual/artistic statement.

Later 19th-century Andean textile art recalls an aesthetic often praised by collectors focused on the art of the Old World, as a Tari Coca Cloth (lot 599) showcases a rhythmic harmoniously conceived palette of alternating colorful horizontal stripes with two red shades, an apricot shade, a light yellow and natural grey alpaca wool – inevitably recalling the appeal of certain Anatolian flat weaves. Four 19th-century ceremonial mantles (lots 603, 605, 606) were woven with a similar visual impact – the use of colorful horizontal bands, plain broad bands of color alternating with broad decorated bands essential symbols of heaven, earth, and more – is exceptionally pleasing. Lot 603 could easily pass for a Navajo weaving from the North American Southwest. Completing this exceptional group is a matrimonial dress (lot 605) with a pleasing palette as the dominant red dyes find welcome contrast with light yellow and sea blue/green bands woven with intriguingly beautiful repeating designs of significance to these Andean cultures.

Later 19th-century Andean textile art recalls an aesthetic often praised by collectors focused on the art of the Old World, as a Tari Coca Cloth (lot 599) showcases a rhythmic harmoniously conceived palette of alternating colorful horizontal stripes with two red shades, an apricot shade, a light yellow and natural grey alpaca wool – inevitably recalling the appeal of certain Anatolian flat weaves. Four 19th-century ceremonial mantles (lots 603, 605, 606) were woven with a similar visual impact – the use of colorful horizontal bands, plain broad bands of color alternating with broad decorated bands essential symbols of heaven, earth, and more – is exceptionally pleasing. Lot 603 could easily pass for a Navajo weaving from the North American Southwest. Completing this exceptional group is a matrimonial dress (lot 605) with a pleasing palette as the dominant red dyes find welcome contrast with light yellow and sea blue/green bands woven with intriguingly beautiful repeating designs of significance to these Andean cultures.

As one might understandably pause to catch one’s breath, a few European textiles complete the sale. A lyrically pleasing English wool embroidered coverlet with an ascending curvilinear tree of beautifully conceived branches bearing flowers of different design types and colors is a pleasing textile – amazingly detailed with small leaves and flowers intermittently emerging the textured surface of the bark. It recalls the majesty of textile art produced on the subcontinent over which they once held sway in the distant past.

As one might understandably pause to catch one’s breath, a few European textiles complete the sale. A lyrically pleasing English wool embroidered coverlet with an ascending curvilinear tree of beautifully conceived branches bearing flowers of different design types and colors is a pleasing textile – amazingly detailed with small leaves and flowers intermittently emerging the textured surface of the bark. It recalls the majesty of textile art produced on the subcontinent over which they once held sway in the distant past.

Antique rugs and textile art are a living document of not only the cultures from which they have emerged but to the very core of the human experience. Written language was unknown to many of these weavers, simple women often ensconced in a rural or semi-rural environment engaged in a subsistence-oriented life with few frills or distractions other than what they could create on a loom or with needle and thread. And to whom were they communicating through their efforts? Their daughters and the next generation of weavers. And ultimately for our viewing pleasure as well. We hope you enjoy these groups of tribal weavings and textile art as much as we have enjoyed putting this important and monumental auction together.