Material Culture is Honored to Offer the Inspired Works of Philadelphia Self-Taught African American Artist, Milton Jews, in the Upcoming Auction:

FOLK OUT LOUD | Fine, Folk, Outsider & Ethnographic Art

Online* Auction: Monday, January 23, 2017, 10AM EST

Exhibition: January 21-22, 11AM-5PM

*Also accepting Phone and Absentee Bids

Browse the Auction Catalog and Bid Live on these Portals:

Absentee Bid Form | Telephone Bid Form | Terms and Conditions (PDF)

Browse the Virtual Print Catalog

“Each Piece Has Its Own Story to Tell”

The Carved Canes of Milton Jews

By Glenn Hinson

Folklore Program, Dept. of American Studies, University of North Carolina

As he moved into his late sixties, Milton Jews—who was born in 1932, and had been carving walking sticks for more than a quarter of a century—found fewer and fewer reasons to travel to his cellar workspace. By the turn of the millennium, he rarely stepped down into what he had long called his “retreat.” “I feel like a stranger to it,” he admitted at the time. “It’s like something’s . . . missing. And I couldn’t tell you what.” Now, Mr. Jews lives in a home for the aging. The canes, he says, are no longer his concern. “They’re part of a life that’s not mine any more,” he explains. “Now they’re just scraps and pieces. And it’s too hard to make people see what I see in them.” His family, in turn, has decided to share them with the public, with hopes that Mr. Jews’ artistry—hidden for so long—will find an audience who will “see what he saw in them.”

2. “Those two there,” said Mr. Jews about these canes, “I made them spoofing the fellows always talking about how they was endowed.” Roland L. Freeman, © 2001. Reprinted with permission of the artist.

That seeing isn’t at all difficult. The walking sticks embody the rather remarkable legacy of an artist’s creativity in an African American urban setting. Seeing this many pieces by a single self-taught carver is itself unusual; that these pieces come from Black Philadelphia makes them even more singular. Most walking stick carvers whose work has been documented come from rural areas, and particularly from the rural South. Their sticks tend to feature natural motifs (snakes, lizards, trailing vines) and human forms, with periodic forays into carved commemorations (e.g., lodge emblems, or references to military service). African American carvers have historically deepened this tradition by adding other media to their sticks, inserting jewelry, sequins, and glass beads to lend sparkle and dynamism to the moving staffs. Milton Jews’ canes—in stark contrast to their rural counterparts—are decidedly urban . . . though still quite markedly African American in their aesthetic choices. Leaves incised into the wood still testify to the sticks’ prosaic origins, but now the foliage cradles carved bullets and astrological symbols. Relief carvings of playing-card suits and chess pieces recall summertime game-playing on South Philly stoops, while recurrent death’s heads and dollar signs invoke the hustles of the street. So too do strings of carved numerals, suggesting the running risks of the city’s numbers racket. Stylized ankhs, clenched fists, and incised hair picks attest to a Movement consciousness, as does the recurrent presence of sculpted screws (pointing not too subtly to African Americans’ experience of the police and the system they represent). Carefully coiffed Afros top the heads carved on many of the cane mounts, while others sticks boast metal, glass, and wood crowns—found objects claiming new meanings. More than one stick bears a fierce devil’s head at its apex, simultaneously a symbol of defiant bravado and a reminder of wrong-headed life paths. Other canes culminate in immaculately carved penises, Mr. Jews’ winking nod to the boastful talk of neighborhood men. From every angle, the sticks’ carved themes speak to the style of Black city streets.

The canes’ shafts, in turn, often personalize this style with solitary words, terse phrases, or the names of those who inspired the designs. The carefully sculpted letters sometimes invoke the tight precision of typesetters’ blocks; in other cases, they capture the whimsical freedom of graffiti tags. Many of these whittled words are names (including those of Mr. Jews’ wife Jennie, his son Charles, and—in a rather remarkable self-portrait stick—himself, declaratively captured in his childhood name, Oliver). Other words poise messages aimed directly at the streets; a devil’s head cane, for instance, pointedly catalogues the seven deadly sins, with “lust” earning the most prominent placement. The foregrounding of carved words lends further singularity to Mr. Jews’ sticks, accentuating their performative nature by catching the eye and inviting it to linger, thus underscoring the identity-messages that the sticks convey.

3. The straps on these canes—meant to be slung over the shoulders or cradled in the arm—testify to their use as affirmations of identity. Roland L. Freeman, © 2001. Reprinted with permission of the artist.

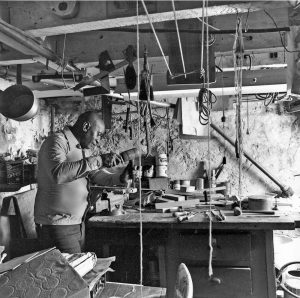

The mixing of media—so characteristic of African American stick carving traditions—also makes its claim in Milton Jews’ canes. While his early sticks boasted only carved and varnished wood (albeit sometimes with found-object crowns), his later ones increasingly incorporated wood-burned details, color staining, beads, and metalwork. Over the years, metal—salvaged from scrap at Mr. Jews’ longtime workplace, a company that made roller coaster cars and carousels—came to play an integral role in his walking sticks, providing both decorative banding and eye-catching details. After teaching himself how to cut and mold aluminum, he began accessorizing his sticks, adding glistening fangs to a cobra’s mouth, bold eyeglasses to a bearded bust, a Star of David atop an elegantly knotted shaft, and even a twisted horn that transformed a horse’s head handle into that of a unicorn. The metal, Mr. Jews explained, made the sticks “come alive,” grabbing the glint of the sun as they moved down the street, while highlighting the flash and style of those who carried them.

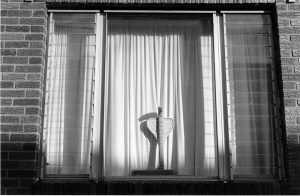

Note the term “carry” here, as this is important when considering Mr. Jews’ canes. While some of these sticks have handles clearly shaped to hold one’s weight, many others just as clearly do not invite a hand’s load-bearing grasp. The sharp horns of a devil’s head, the slender neck of a brass egret, or the spiked ears on a fanciful winged serpent all actively resist holding. Perhaps that’s why Mr. Jews never referred to his canes as “walking sticks” . . . because the burden that so many bore was not meant to be that of the body, but that of their carrier’s style. In Mr. Jews’ words, the sticks were meant more for carrying than for walking. Hence the cord attached to so many of the canes’ shafts, a cord that allowed the carrier to slip them over a shoulder, and thus to wear them as one would a piece of clothing. Carrying a stick became an act of performance, a public proclamation of one’s identity, a declaration that offered carved clues to the sensibilities therein. “It’s how you expressed yourself,” Mr. Jews once reflected. “The stick just sets it off. You was considered dressed then.”

In addition to marking the carrier’s style, the sticks also filled the added function of protection, a quality not always unimportant on the streets of South Philly. “Notice the weight it’s got to it,” Mr. Jews mused more than a quarter of a century ago, while shifting one of his heftier canes from hand to hand. “Nobody’s going to mess with you when you’re carrying one of these.” Carried proudly over the shoulder, the walking stick served as both witness and warning.

4. “Now when I look back on it,” Mr. Jews mused in 2001, “it’s hard to believe that I spent that many hours down in that cellar, and was so happy doing it.” Roland L. Freeman, © 2001. Reprinted with permission of the artist.

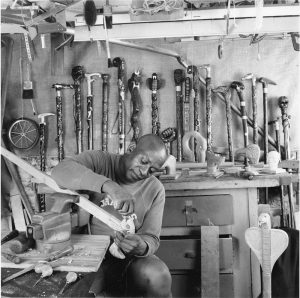

While Milton Jews crafted some sticks for neighbors and friends, he seems to have carved most for himself. Carving was his way to—in his words—“escape” from day-to-day concerns and struggles, and to follow a “calling” to capture meanings in wood. He described stepping into the cellar as a stepping away from both family responsibilities and the repetitious rigors of his factory job. “In my mind,” he reflected, “it was like a trip. You’re looking for something. Or you’ve found it, but you’re trying to develop it.” That “something” for which he was looking was a very particular kind of communion, a connection with the wood that lay before him, one that he hoped would lead him to discover the hidden forms that the wood held.

“See, each piece of wood has its own story to tell,” he later explained. “And I’d call myself looking for the soul of the wood. Cause the wood talks to me. And then you start to see these things in it—you can’t tell people that, because the first thing they say

Working initially with chisels and rasps, Mr. Jews would chip away at the future shafts and heads with spirited intensity, quickly slipping into what he called his “zone.” In just ten minutes, he recounted, “I could have almost a shopping bag of chips.” As the shavings piled on the floor, and the wood began to reveal its secrets, the work began to feel more and more satisfying. “When you’re trying to make the statement, or bring out what you’re looking for, it feels exciting,” he later recalled. “Because up to that point, you only see this in your mind. See, and to bring it out . . .” He paused, and just shook his head, not finishing his thought. But the meaning was clear. To “bring it out” was to realize a vision that was ultimately shared with the wood, to “make it come alive,” to catch its spirit. As the sought-after form emerged, Mr. Jews would lay down his chisel and begin carving with a knife, the flying chips giving way to slowly emerging curls. He describes this part of the work in the most sensual of terms, as if each draw of the knife was a caress. Those caresses—repeated many hundreds of times for each stick—led him speak about his finished pieces as his “children.”

5. “I’ll get in my most creative moods when I’m here by myself,” remarked Mr. Jews, reflecting on decades of solitary woodcarving. Roland L. Freeman, © 2001. Reprinted with permission of the artist.

I first heard Mr. Jews use this term in 2001, when I asked him about a striking photograph taken of him working in his cellar by the acclaimed African American documentary photographer, Roland Freeman. The image—which features many of the canes now being auctioned by Material Culture—was part of a documentary project sponsored by National Geographic magazine and the Smithsonian’s Office of Folklife Programs (now the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage). It first appeared in the Smithsonian-sponsored exhibit “Stand By Me: African American Expressive Culture in Philadelphia,” which opened in 1989 at Philadelphia’s Afro-American Historical and Cultural Museum. The image also assumed a prominent place on the project poster, graced the cover of the exhibit’s catalogue, and appeared in Roland Freeman’s National Geographic photo-essay.

When I visited Mr. Jews more than a decade after the exhibit, having not seen him in that intervening time, I was struck by the fact that framed copies of both the poster and the catalogue still hung on his living room walls. I had last seen those walls when the photograph was first taken, shortly after I—a white folklorist who was part of the original project team investigating vernacular artistry in Black Philadelphia in the late 1980s—had introduced Mr. Jews to the photographer Roland Freeman. Acknowledging the carefully arranged centrality of the framed images, I asked Mr. Jews about the photo’s importance to him. His answer was quick and unequivocal: “That’s my family portrait. That’s the most real family portrait that’s ever been taken of me.” Puzzled, I pressed for elaboration. “Because these are my children,” he declared, pointing to the canes arrayed in the photograph. “It’s a funny thing, but each one of my pieces was like a child. That you nurtured. See, because you’re developing all these little—these little pieces. You’re living with them! You’re living with them.”

“So it’s about the time that you spent working on each stick . . . ,” I suggested.

“It’s not just the work, per se,” he responded. “It’s what you feel, what you put into it. To get that,” he continued, pointing to the sticks, “you have to put love in it, in order to get it out. You see? Now, you love your children—but they’re really your wife’s children. But when you do something like this, that’s yours. Individually yours, you see.”

6. Milton Jews proudly displayed this standing python—which he called his “masterpiece”—in the front window of his South Philadelphia row house. Roland L. Freeman, © 2001. Reprinted with permission of the artist.

Perhaps this explains why Milton Jews never sold his canes, except to those few friends in the neighborhood who had commissioned specific pieces. But the sticks never went to outsiders. Even after Mr. Jews gained a measure of public recognition from the “Stand By Me” exhibit, even after he was recognized by the Pennsylvania Heritage Affairs Commission for his mastery as a woodcarver, and even after he contributed a piece to the much-acclaimed “Uncommon Beauty in Common Objects: The Legacy of African American Craft Art” exhibit (whose national tour included showings at the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery and New York City’s American Craft Museum), he rejected all monetary offers for his sticks. They weren’t made to be sold, he asserted. Because they were “family.”

Interestingly, the canes’ full status as “family” seems to have emerged during the session in which Roland Freeman made his iconic photo. When Mr. Jews first stepped into his cellar that morning, no canes were evident; only carved heads—not yet mounted on shafts—defined the workspace. (One of the heads evident in the photograph—that of a crook-necked vulture—served as the model for a second, more detailed and more sinister head that tops one of the sticks in the Material Culture collection.) When asked if he could bring down a few finished canes, Mr. Jews stepped upstairs and returned with an armful of five. After laying those on a table, he turned again to the stairs, declaring that he wanted to get some more. That second armful gave way to a third, and then a fourth, ultimately yielding the eighteen sticks that grace the photograph. Some, Mr. Jews reported, had been in closets; others were under beds; only a few were out and easily accessible. He seemed surprised to see them all together.

As it turns out, he was surprised. Years later, Mr. Jews revealed that he had never actually set so many of his sticks side by side. “It was interesting to me to see [them] all,” he observed. “‘Cause I’d never seen them. Never had that many sticks out. Never. Never even thought about it. It’s just a thing that . . . it just never entered my mind. Because you know what you got. So I didn’t have to do that.”

But maybe he actually did “have to do that.” In a later conversation, he spoke again about that moment, adding reflectively, “That’s when I saw my family. Yeah. All my children.”

7. Milton Jews and his wife, Jennie Mae Jews, in 1988. Roland L. Freeman, © 2001. Reprinted with permission of the artist.

When tracing the origins of this “family,” Mr. Jews quickly points to his own childhood, and to the artistic inspirations offered by his mother and his aunt. Born in 1932, Milton Jews spent his first year in Cecil County, Maryland, a county at the upper reaches of the Chesapeake Bay, and one whose northern and eastern borders tellingly defined the Mason-Dixon Line. Before he was two, however, his mother moved him and his two siblings northwards along the Great Migration path to Philadelphia, where they joined his mother’s older sister in an already-crowded South Philly row house. The neighborhood’s overcrowding grew palpably more evident with each passing week, as trainloads of hopeful Southern migrants—much like the Jews family themselves—streamed into the city, fleeing Jim Crow repression and seeking promised-land opportunity.

Growing up, the young Milton Jews found himself living in a world defined by both struggle and epiphany. At every turn, he faced the desperation of families (his own included) trying to get by in the heart of the Depression. (His mother, aunt, and older sister all labored in some form of domestic service, while his teenage brother did pick-up work and his cousin toiled as a stevedore at the nearby wharves.) At the same time, he everywhere encountered the humanity-declaring artistry of Black performance, whether in the sartorial splendor of marching believers in the city’s Daddy Grace parades, in the lilting chants of the horse-drawn vegetable vendors who plied the South Philly streets, or in the quiet whittling and artful talk of men who passed their days on row-house stoops. Mr. Jews seems to have taken particular note of those streetside whittlers, whom, he recalls, “were quite common” in the neighborhood. Indeed, he attributes these whittlers—and later, his brother’s work in a casket-making shop—with fueling what he came to call “that old wood bug—my fascination with wood.”

Interestingly, while noticing the neighborhood’s many carvers, Mr. Jews does not remember seeing many carved canes. Other residents’ accounts, and a number of surviving sticks from this period, suggest that intricate sticks were, in fact, an important part of the Depression-era Black Philadelphia streetscape. But they apparently didn’t catch the eye of the young Milton Jews, who later recalled only the metal-topped “gentlemen’s canes” that so clearly inspired many of his own ornate mountings. His young gaze seemed to have focused more on the process of carving—on that careful communion of eye and knife—than on the carved products that so showily plied the city’s streets.

When speaking of his childhood, Milton Jews describes himself as a “sickly boy,” noting that immune-system problems kept him confined him to his bed for long stretches of time. His mother and aunt, in turn, “had to find something to keep me in bed. So they whittled my mind into drawing.” Both of them encouraged him to try his hand at sketching, a practice that he pursued with youthful passion, and one that fostered a life-long love for creative expression. “After that, I was always making things,” he remembers. “Drawing, carving, taking pieces of this and that and making something out of them—that’s just what I did. . . . I would just pick up whatever was around me and use it to some degree.”

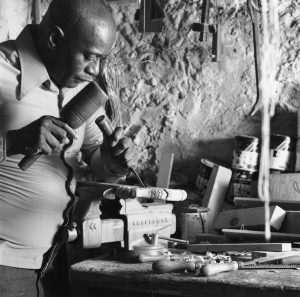

8. In addition to carving canes, Mr. Jews also sculpted a few larger pieces, including this painted and varnished bust. Roland L. Freeman, © 2001. Reprinted with permission of the artist.

The connection between this “picking up” and actually working with wood was likely forged when Milton Jews was only twelve, when he got his first paying job gathering scrap wood from around the neighborhood to fuel people’s stoves in the lean wartime years. Even at this young age, he began to notice the smells and textures of different woods—an awareness that he further honed in his mid-teens, when he began “hanging out” at the funeral supply company where his cousin worked making casket tops. Mr. Jews speaks about that time as an informal apprenticeship, one in which he learned the ways of wood, to the point where he could “make a casket from scratch” by his late teens. “Even then, working with wood just seemed like second nature to me,” he later recalled. “If you’ve ever smelled pine like I smelled pine—it just grew in me. And it never left.”

But opportunities for gainful employment while working with wood—or working with anything, for that matter—in post-war Philly were scarce for inner-city Black teens. So at age 17, Mr. Jews joined the Army, ultimately serving for six years (fully half of which were apparently spent in and out of hospitals, as breathing problems forced a series of lung operations). When he mustered out, he quickly discovered that little had changed back home; jobs were seemingly as sparse as ever. Again, he turned to pickup work, looking for worksites that would feed his aesthetic sensibilities, ones that invited a measure of creativity rather than demanded a routinized mindlessness. He found one—for a brief period—at a local letterpress printer, where he came in contact with craftsmen who carved the wooden letters used in the presses. Intrigued, Mr. Jews stole time away from his assigned tasks to watch and learn. As with his casket-making, he proved himself a sharp student, and soon found that he could match the carving skills of his informal teachers. Though he had never carved in relief before, his whittling repertoire readily expanded in this direction, a development amply evidenced in the meticulously carved letters on canes that he was to craft decades later.

Mr. Jews’ occupational path from the late 1950s into the 1980s is, by his own admission, something of a blur. He studied commercial illustration at a Philadelphia art school for a few years, only to discover that job opportunities for African American illustrators simply didn’t exist. So he worked at a variety of factory jobs, doing everything from making caskets (again) to constructing Skee Ball games and fashioning wooden parts for roller coaster cars.

At one point in the late 1960s, when Mr. Jews was doing millwork at the Philadelphia Toboggan factory, he caught sight of a glinting piece of metal in a trash pile. “I looked, and there was a silver tip stick,” he later recalled. “That’s what really started me carving [canes], when I picked this off the trash. See, the shaft was deteriorating. And I was going to make—[I was] thinking about the old gambler pictures, when you seen the silver-tipped cane—I was going to make that stick into my crowning piece.” And he did. Beginning with a thick shaft, he carefully whittled the wood down, adding shapes and letters until it found its final form. “I wanted to make the wood come alive,” he remembers. “So I carved it deep, so you could feel it.”

9. “There’s an art to walking with a cane,” reflects Mr. Jews. “Each one has its own personality.” Roland L. Freeman, © 2001. Reprinted with permission of the artist.

That stick offered an alternative to the repetitious machine-milling of the factory, and promised a path where Mr. Jews’ creativity could freely unfold. From that moment forward, carving canes became his creative outlet. Sticks increasingly offered paths of both respite and play, while his cellar workshop became a place of passion. Mr. Jews would later say that he would leave for work every morning with his mind on the cane that he was carving in his basement. “I still carried that same stick [in my head],” he recalled. “I’m looking at it; I still got different ideas about it. It’s still with me—the impression is that strong. When you come home, you’re laying down all this emotion back into this piece that you’re doing.” That emotion—infused in dozens of sticks created over the next quarter of a century—is what now emerges so powerfully in the canes being exhibited at Material Culture.

By the turn of the millennium, Milton Jews was making fewer and fewer trips to his workshop. Though he had retired by then, and was still physically quite sound, he seemed to have lost the inspiration to carve. Partially carved cane heads rested unfinished on his workbench, while others lay in dusty downstairs drawers. Wood awaiting the touch a chisel littered the cellar floor. But the feeling just wasn’t there. When asked at the time, even Mr. Jews’ couldn’t say what had changed. “But I do know [that] once I break through it,” he asserted, the hope evident in his voice, “I’ll be down there all the time!” Unfortunately, this didn’t prove to be the case. Exquisitely carved canes still filled tattered florist boxes shoved under beds; others hid behind clothes in bedroom closets. And there they stayed.

In early 2015, Mr. Jews’ failing capacities led his oldest daughter to admit him to a nursing home. No carvings traveled with him. Nor did, it seems, any regrets about leaving them behind. By his own accounting, he had entered a new chapter, one in which his life as a carver had grown increasingly unimportant to him. The same was not true, apparently, of his life as an artist. Within weeks, the bland beige walls of his shared nursing-home quarters had come alive with taped-on sketches, penned portraits of remembered and imagined faces, drawn on the backs of whatever scraps of paper he could find. The gallery of drawings—dozens in all—hovered over his bed, framing the bare fluorescent light fixture that lit his side of the room. “I’m back to rendering again,” Mr. Jews excitedly declared last year. “Since I started doing this, things began to fire up, like an old car. . . . This new resurrection of my work is the top thing in my mind!”

10. Sketches from the walls of Mr. Jews’ nursing-home room. “This is the new resurrection of my work,” he notes. Glenn Hinson, © 2015. Reprinted with permission of the artist.

But this “resurrection” is neither as consistent nor as directed as Mr. Jews’ carving. Sketches taped to the wall one day have vanished the next, with Mr. Jews unable to tell where they went or what they had portrayed. Stories about the drawings whisper in and out, present for a moment, suddenly surrendering to a different train of thought, and then perhaps floating back. Some of the inked portraits echo themes present in his years-ago sticks—a devil’s head, a glaring skull, a stylishly hip profile. Around the faces drift other familiar images—clubs and spades, bullets, eyes, trailing vines, and the ubiquitous screw. But no images of canes or carvings appear on the walls; indeed, the only drawings that explicitly invoke wood depict caskets. It’s almost as if the decades of crafting elegant testaments of style have vanished from Milton Jews’ aesthetic memory. Now—to use his words—they’re just the “scraps and pieces” of a life left behind.

Milton Jews’ passionately carved canes, however, tell a story that resists the silencing of memory and time. Like the wood from whence they came (in the mystically discerning eyes of their carver), they offer a testimony that speaks not only to a lone artist’s vision, but also to a community’s aesthetic and sense of self. The connection between the two is perhaps best revealed in the story of Mr. Jews’ workspaces. The factory where he labored when he began carving sticks—as Mr. Jews recalled many years later—was an all-white shop. His was the only Black face. So he kept to himself. He says that he didn’t want to cause any trouble. He didn’t want to draw any undue attention. Hence he followed their rules, and did their work, for well more than a decade. And every day during that time, he came home to the same African American community in which he had grown up, to a house only a few short blocks from the one to which his family had moved when they first arrived in the city. Every day, Mr. Jews stepped by stoops filled with phantoms of long-ago whittlers and their delicately carved testaments; every day, he strode over sidewalks that cradled memories of proud stick-carrying strolls and stylish displays. And when he got home, he slipped into his cellar, his cramped but passion-filled retreat, where he could enact his Blackness, and craft his spirited contributions to its aesthetic. It didn’t matter if the sticks didn’t immediately find their way into the world. He knew that they ultimately would. Children, after all, grow up. And as they mature, they have things to say . . . about their past, about their home community, about the legacy they embody. Maybe that’s why Milton Jews came to call his canes “story sticks.” Because now they each have a lot to say. By gathering them together for the first time outside of Mr. Jews’ South Philly home, and by offering them to the public, Material Culture hopes to provide a stage suitable for their striking stories.