Lehigh University Art Galleries:

Main Gallery, Zoellner Arts Center

August 29-December 3, 2012

Material Culture is proud to announce its partnership with Lehigh University in bringing an exhibition titled “African Visions of Barack Obama: Folk and Popular Images of America’s 44th President” to the Main Gallery of Lehigh’s Zoellner Arts Center. All artworks are part of Material Culture’s collection, though the curatorial staff at Lehigh University, led by Norman Girardot and Ricardo Viera, are to be credited for the creation of the exhibition’s design, installation and contextual presentation. These works transcend politics, and invite us, instead, to focus on what connects us across the globe, and art’s role as a universal manifestation of humanity’s passion and hope. The exhibition will open on August 29, 2012 and run through December 9, 2012.

George Jevremovic, founder of Material Culture, relates that when he first traveled to West Africa in search of textiles and other artifacts, the most arresting pieces of art were in fact the ubiquitous painted signs of folk and popular artists. Dotted on roadsides, emblazoned on businesses, these painted works on canvas, board, metal or on the sides of buildings serve to advertise, instruct, or simply delight passersby. Businesses such as barber shops, beauty salons, tailors, grocery stores and movie theaters have increasingly used hand-crafted banners and placards, recognizing the cycle of communication between the artists, their images, the population, and the society that contains them all. Though advertising creates a clear venue for these artists, many of their paintings are simply, as Jevremovic says, “art for art’s sake,” an expression of the artist’s interests, passion and skill. The artists paint from daily observation and their own imaginations, but their works also frequently include celebrities and folk heroes, from Africa and abroad. Figures such as Bob Marley, Michael Jackson, Kofi Anan, Che Guevera, Nelson Mandela and Jesus Christ constantly resurface; often they appear purely as an artist’s tribute, but sometimes as part of an advertisement, when the client commissioning the piece chooses a celebrity to unofficially endorse their business.

Inevitably, as Barack Obama became the first American with African ancestry to be elected as President of the United States, his image began swiftly to circulate amongst the works of these popular artists. Material Culture’s long appreciation of this artistic tradition led Jevremovic to conceive of a project that would both study and celebrate their artistic responses to this event, and to Obama as an icon. In his 2009 essay, Jevremovic describes his idea to collect “a group of artworks created during and leading up to Barack Obama’s first year in office, sensing that something so seismic, so public, and yet so personal for so many, would find fertile ground among African artists.” He adds, “We were not disappointed.”

This exhibition showcases that collection, comprising 105 paintings and sculptures from Ghana, Kenya and Nigeria. The artworks are diverse in scope and technique, their tone at times humorous, sometimes surreal or majestic. But despite the worldwide potency of political images, these paintings are not about American politics as much as simple pride, hope and celebration, an important point for Lehigh curators Girardot and Vega. As they state in their essay on the show, “This exhibition is not about Barack Obama. It is not about the current presidential election. And it is not about taking sides during a political year. It is about Africans and the revelatory power of the visionary imagination.” The aim, then, is to delight in the imaginative and visual potency of these African artists and the tradition of their work, in the context of the shared, global experience of Obama’s role in American history.

Though some of the artwork in the show were made for businesses—for example, two-dimensional busts of Barack and Michelle Obama, created to peek out of the neck of clothing on display, or a sign advertising “Time Changes hair cut” with paintings of Nelson Mandela, Obama, and Kofi Annan—most pieces are pure artistic commemorations of the man and his achievements. Obamas proliferate, speaking into microphones, to crowds, against American stars and stripes. He is often pictured with others, most frequently Michelle, followed by Sasha and Malia and “Granny Sarah,” Obama’s Kenyan grandmother (in fact, the third wife of Obama’s paternal grandfather). Historical and political narratives place him alongside Martin Luther King, Jr. in D.A. Jasper’s “A Legacy of Hope,” and John McCain in the same artist’s “John McCain Congratulates Obama.” Papa Warsti’s lifelike portait “Michelle Obama, Barack Obama, Joe Biden,” sets all three against an American flag and a rising sun, with the helpful labels USA PRESIDENT, USA FIRST LADY and VICE-PRESIDENT below each figure.

But many of the most provocative renderings stem from a re-contextualization of Obama’s figure in visionary scenarios. A few artists seem to have the desire to depict Obama in motion, perhaps a visual embodiment of his political momentum. In Isaac Azey’s “New Dawn,” a running Obama carries aloft a torch and an American flag in each hand, while one of three untitled works by Laty shows Obama riding headlong into the viewer’s perspective on a slightly tilting bicycle. D.A. Jasper puts him astride a white horse in “Obama on his way to the White House,” and then, like Laty, a bicycle, in his painting “The Great Pupils Lover.” One of the exhibition’s most delightfully surreal pieces, the latter shows Obama on a bicycle laden with books and with a small black dog, leashed to the bars, in tow. Subtitled “Barack Obama on his bicycle Ride from Africa to the White House,” Obama and his dog pass a row of black skyscrapers against a red sky, with the President pointing towards the road’s upward curvature and the place where the dome of the U.S. Capitol building appears to be bursting through both space and time in the far right of the canvas. The same kind of surreal vanishing point appears in Bright Obeng’s “Congratulations Mr. Obama,” in which the President, while shaking one of the hands that emerge in a ring from the frame, stands on a ramp that leads straight into a blue clouded sky reminiscent of Rene Magritte.

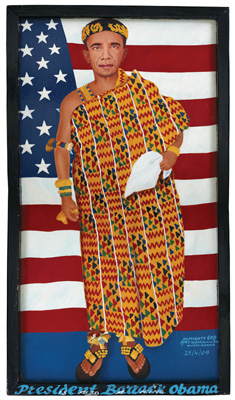

Another recurring theme is the recostuming or redressing of Obama; Stephen Duah’s affable, photographic Obama appears in a green African shirt, while Kwame Akoto, known as an artist by the name “Almighty God,” robes the President as an African king in front of a gigantic American flag in his painting, “President Barack Obama is Also a King.” In an extremely compelling mixed media piece that blends the tradition of painting and collage, the artist Ibrahim Iddrisu suits Obama in a superhero’s jumpsuit and cape. Entitled “Obama as Superman,” the painting fills the shape on the President’s chest that would hold Superman’s “S” with a found illustration of happy, multiracial families collecting a harvest and enjoying nature in an Arcadian ideal. The river in the found image is echoed in the blue river that glitters past Obama’s shoulders; behind him, a path leads to a hut with a photograph of two young African boys pasted to stand in front of it. Other found images of people and animals inhabit the land on the opposite bank, below the heads of palm trees.

Some of the artworks’ metaphorical storytelling come with fascinating backstories. Sheff’s unfinished portrait of Obama carries a deep vibrancy, emotional resonance, and allows for a complicated dialogue with any viewer. A canvas of commanding size, the lifelike painting trails off above Obama’s mouth, below which an uncolored sketch outlines his lips and chin. The dark background seems to seep from the top to drape his head, dripping into the white space beside his unfinished ear. Jevremovic, in his essay, brings up the striking resemblance to Gilbert Stuart’s (1755-1828) unfinished portrait of George Washington; in Stuart’s case, however, he intentionally left the canvas incomplete as a model for future portraits of Washington, while Jevremovic narrates the discovery of Sheff’s piece as being quite different. Coming across Sheff’s roadside studio featuring a series of portraits of Obama in different artistic attitudes, Jevremovic found the “raw poignancy” of the unfinished canvas drew the most attention. “Sheff offered to complete his Obama,” Jevremovic writes. “He seemed amused more than surprised when we told him that we’d be happy—as long as he agreed—to purchase all the paintings as we found them. ‘No problem,’ he replied.” This fortuitous timing brings to us a stunning piece, where the unfinished mouth may symbolize to the viewer the unknown future, our country’s history as a work-in-progress, or perhaps even the difficulty of discourse—meanings not crafted by the artist’s hand, but inviting the audience’s completion of the unfinished piece with their own interpretation. Throughout the show, the audience is in dialogue with the vibrant outpouring of the African artists’ imagination and craft, but also discourses with its own ability to see, to interpret, and to understand. In their essay, Girardot and Viera explain that the primary concern of the show is “the morality of empathetic knowing – to see the world as others see it. This is the ability to know that by imagining the world through different cultural lenses we simultaneously learn something about that other culture, about ourselves, and about the deepest and most responsible art of seeing and knowing.”

The run of the exhibition will include a reception and gallery talk by George Jevremovic on September 20, at 5 PM, and a lecture on folk art by Henry Glassie, folklorist and Emeritus Professor at Indiana University, on November 15, at 5PM. The Zoellner Arts Center’s Art Galleries are located at 420 E. Packer Ave. in Bethlehem, PA, and are open from 11 AM – 5 PM Wednesday through Saturday, and Sunday from 1 PM – 5 PM. The galleries are free and open to the public. For more information, call the Zoellner Arts Center at 610-758-3615.